EAL learners are not a homogeneous group. However, it is helpful for teachers to conceptualise the overall or 'macro' task for pupils learning EAL. This will help to develop their understanding of what is distinctive about EAL within education.

EAL learners are not a homogeneous group. However, it is helpful for teachers to conceptualise the overall or 'macro' task for pupils learning EAL. This will help to develop their understanding of what is distinctive about EAL within education.

It is very important that policy, planning and teaching decisions at all levels always take account of the task for the learner. Viewing the task from the learner's perspective can be seen as an essential element of being meeting the Teachers' Standards. Yet it is easy to lose sight of the learner's perspective. There are two main reasons for this:

- Once pupils learning EAL have acquired a very basic communicative competence, it is easy to assume that their understanding of English and engagement in learning is much greater than it actually is

- Pupils with EAL are learning in mainstream classrooms where the needs of all pupils have to be met. It is not always possible for teachers to take account of the distinctive learning situation of pupils learning EAL. If EAL were a separate subject (like a modern foreign language) the raison d'etre for the class would clearly be learning a language; this is less clear for pupils with EAL in the mainstream context. Neither the adults attending a language class in an F.E. institution nor their teachers are likely to forget either the purpose or the difficulty of their task. Yet in the context of the mainstream classroom, it is easy to lose sight of the EAL learner's task.

How can the EAL learner's task be conceptualised? It will vary from individual to individual, depending on such factors as age, educational and cultural background, and socio-economic status. However, by taking an example it is possible to highlight common factors and enable variables to be more clearly identified.

There are many children starting their formal education in the nursery or reception class who come from settled communities and who are at the earliest stage of learning English. Let us assume that such a child is called Sabeela. What is the task that faces her?

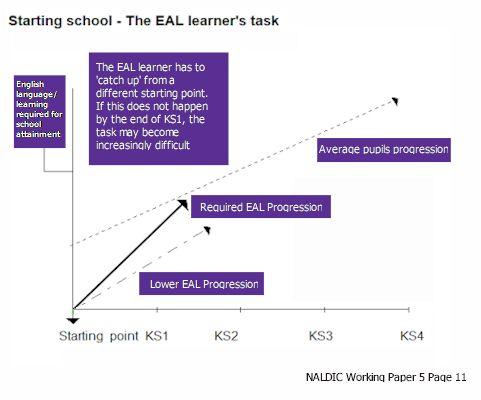

We all know the incredible progress nearly all children have made in learning their mother tongue by the time they are five years old. It is a level of language development that is assumed to be in place for educators to build on. It has taken place for Sabeela too, but for her it is in a language which is not used in school. So, as the diagram below shows, her starting point is different.

Sabeela's primary task is to learn English. At the same time she will need to:

- engage in learning through the curriculum;

- go through the daunting process of learning to socialise with children in the language she has yet to learn;

- learn the social practices of the classroom and the school which are culturally embedded. These are likely to be far less consistent with her home background than for the majority of children.

We know how important the early years are for children's cognitive development. Much of the significant growth in the acquisition of new concepts takes place through children's knowledge of language. However, the linguistic basis of much of this new learning is not accessible to Sabeela. At the same time, the use of her first language is likely to be increasingly unavailable to her in the school setting so that the language which has so far been a central aspect of her development in the home will have little significance for her as a learning tool in school. In terms of the educational setting, she may be effectively cut off from the cultural and cognitive content already established through her mother tongue and which has shaped her identity. Her school experience will radically alter this identity.

So, Sabeela's immediate task is to be able to learn when the most significant means for learning, her mother tongue, is in large part inaccessible to her. More than this, her task is to 'catch up' with the other children quickly. If she manages to approximate to this by the end of Key Stage 1, she may do well in the education system, although it is important to remember that her development in English will not be complete at this stage and will require continuing support. But if she fails to make sufficient progress by this time, her task is likely to become more difficult because the demands of the curriculum depend increasingly on literacy skills in English, and on the knowledge which the children have acquired in school. And 'catching up' is basically her problem. No-one waits. The curriculum moves on. Sabeela is faced with a moving target.

This example has highlighted the task facing the EAL learner:

- to progress from a radically different starting point from other children;

- to learn a new language;

- to learn the curriculum in a new language;

- to acquire the appropriate social skills;

- to accommodate the new language, values, culture and expectations alongside the existing ones she has learned at home.

This has to be achieved in a relatively short time, and attainment will be measured against a constantly moving goal or target. Relative to the learning task that faces the majority of children, this is clearly a 'distinctive' task.

Similar diagrams could represent the task for pupils at different ages. For older pupils who enter the education system with different home and educational experiences, the task will vary. The school curriculum increasingly requires an understanding of abstract concepts, relying heavily on previous knowledge, literacy skills and an ability to work independently. Learning will tend to have less contextual and interactive support than for a child of Sabeela's age. But whatever the age of the pupil's entry into school, the distinctive nature of the EAL learner's task is to 'catch up' with a moving target by engaging in learning an additional language simultaneously with learning the curriculum content, skills and concepts. In addition, while rates of progress will depend on a range of variables, the learning and social context within the school will play a part in making the task easier or harder.

Mapping the 'macro task' from the EAL learners' perspective, taking account of their starting points, will help student teachers to understand the learner's situation and to plan teaching strategies which are appropriate for EAL learners.

Adapted from Working Paper 5: The Distinctiveness of EAL: A Cross-Curriculum Discipline. (1999) Watford : NALDIC

Editor

Nicola Davies

Last updated

January 2012